This is not merely reflexive. The long static shot reshapes modes of attention, revealing that over time, what appears to be nothing of significance happening in the frame, is instead a highly complex document, with much going on that was not immediately apprehensible visibly or otherwise. Such durational, real-time cinema attempts to equalize each moment as part of the continuous flow of time, allowing viewers to find the meaning in an event in relation to their own perceptions and intellectual processes. It provides an ethical dimension to the recording of an event by making time noticeable as a material aspect of an event. The continuousness of the durational shot verifies the authenticity of what was recorded, as it not only shows what was in front of the camera at the time of recording, but it also shows time passing. The continuous video smartphone recording of the murder of George Floyd generates an increasing awareness of how long one is watching Police Officer Chauvin strangle the already handcuffed Floyd with his knee as he pleads for his life. While one cannot see death, one can experience the time it took to kill him. The resounding chant across the country: eight minutes and forty-six seconds, is not only testimony to how long it took to kill Floyd, but also to the experience of the time it took to watch it. I would argue that it is not just that one is seeing the pressure of Chauvin’s knee on Floyd’s neck, but it is also experience of the pressure of time passing as one watches Floyd dying. Time to think minute by minute of the range of choices that could be made by Chauvin and the other police at the scene during that time. Viewers themselves become implicated, both as voyeur of the spectacle of another Black death, and perpetrator, unable to act to stop this. All create a physical and embodied reaction to the experience. Using the pressure of time experienced in the recording, the Rev. Al Sharpton, as part of his eulogy at George Floyd’s funeral, exhorts attendees to stand silently for 8 minutes and 46 seconds, to physically experience the length of time it took Chauvin to kill Floyd. This performance of the pressure of time evokes the materialist aesthetics of the Modernist avant-garde in John Cage’s 4’33” (1952). The silence of the composition, over time, reveals the social dynamics and sonic richness of the event taking place as the audience experiences the heightened awareness of being present in time.

The emergence of the continuous shot of long duration as a formal mode of observational documentary disrupts the spectacle of the visible with an experience of the materiality of time. One thinks of the observational documentaries of Wang Bing, Sergei Loznitsa, Chantal Akerman, Harun Farocki, among others. Like the highly formalist avant-garde films long associated with Warhol, Snow, Akerman, Benning etc., this durational form of observational documentary re-inhabits their Modernist aesthetic of askesis—the stripping away non-essential layers of artifice—moving toward disillusion. Here, cinematic time becomes increasingly material as the embodied experience of being in time as a phenomenon of the present.

As with the Structural-Materialist films of the avant-garde, the use of the continuous durational shot in contemporary observational documentary moves from being about something toward an experience of something. In its purest materialist form, this suggests the film is an index of its coming into being and therefore does not represent anything. The time of the durational image brings forth its graphic elements as composition, its flat surface, light, texture, color, and relationships between inside the frame and outside as it all changes over time. In a less pure way it creates awareness of the dialectic or tension between these material elements that constitute the film object, and the image as a representation of what was in front of the camera. This happens over time, intellectually, as one is compelled to think about such relations, but also autonomically, as one experiences the force of time on the body, which can become an index of consciousness itself.

Similarly, the long duration shot is also revelatory—that which has once gone unseen or unnoticed, over time becomes visible. We come to see more and more of what is there, often pushing beyond the visible to include that which surrounds the image beyond the frame. Within the undifferentiated flow of time, the real-time single take shot also reveals the present moment as always having the potential for something meaningful to occur. The growing awareness of the contingency of the present moment, often produces the sense of suspense, intensity and drama of an event that may or may not arise from the flow of time. This at once produces a sense of distance in undifferentiated time, and the absorption of narrative emplotment.

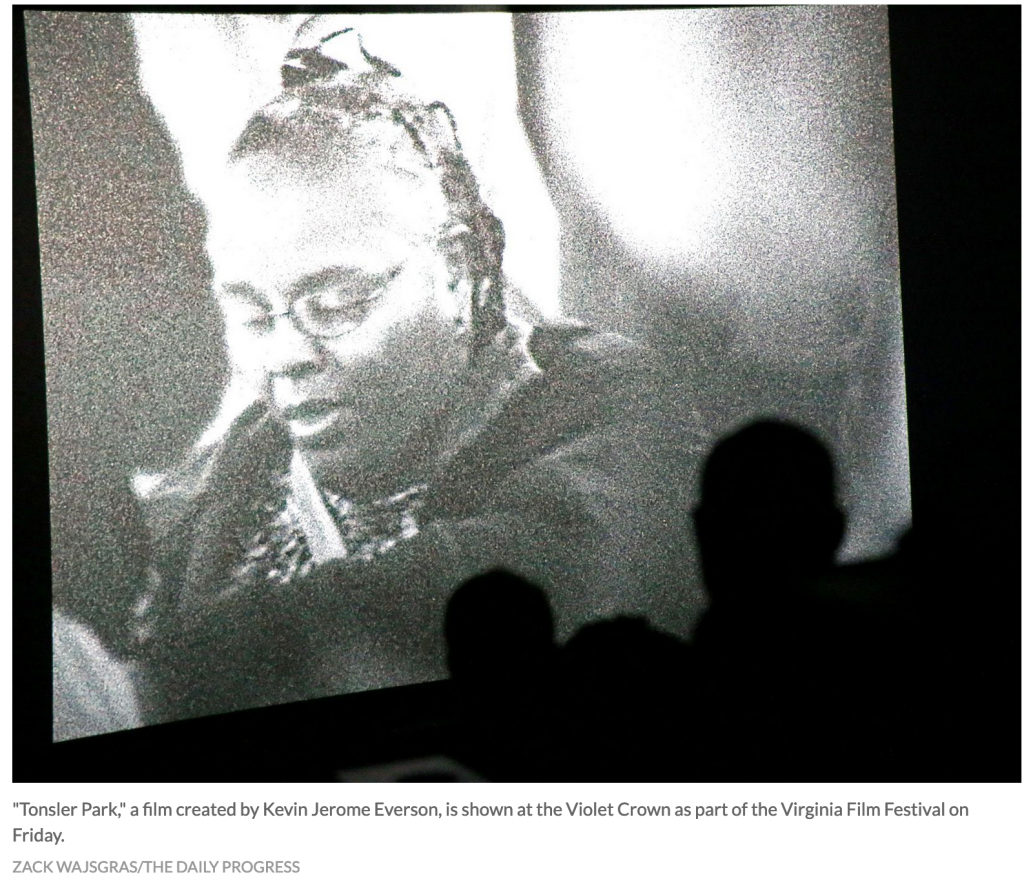

Tonsler Park, (2017, 80 mins.) for example, Kevin Jerome Everson’s documentary portrait of African American poll workers—mostly women—at a polling place in Virginia, uses long continuous static shots of the poll workers checking voter’s registrations, signing them in and giving them ballots as they move toward the voting booths. Shot mostly in close up, we see the faces of these usually unnoticed poll workers, observing what at first appears to be their mundane and repetitive work, but over time one begins to notice the seriousness, attention and level of focus with which the work is being done. We feel the quiet rhythms of the day and see the strong sense of purpose. One notices the earnest social and interpersonal interactions that go on between the workers and voters. This is what democracy looks like. Over time the scene opens beyond the moment itself toward the history of African American struggle for voting rights, the history of voter suppression and harassment and the then recent, regressive striking down of central parts of the 1965 voting rights act by the Supreme Court. The camera remains static over time as voters move in and out of the frame, and despite the prosaicness of the activity in the room, one begins to understand why these poll workers are so committed to their work. The duration makes their work visible as part of the process of struggle for the right to vote that has been going on for 150 years, something we now see the workers clearly do not take for granted. We experience in real time that in fact there is nothing prosaic about anything going on in the room, that this seemingly mundane activity is in fact revealed as an event of historical proportion, not to be taken for granted.

The avant-garde modernism of Warhol and Cage et al, insisted on an awareness of the aesthetics of time. The durational observational shot is an embodied experience in which watching an image increases an awareness of being in present time. What the durational shots of both the rigorously formal work of Tonsler Park and the spontaneously made document of the murder of George Floyd also reveals is the temporality of a political urgency–which can no longer be ignored. How much time a viewer is willing to look at such images becomes a determinant of what is seen and thought. The willingness to take that time lies in the ethics of the viewer.

Join the conversation, leave a comment on the discussion board