In March 2018, eager to share our emerging method with more colleagues, we facilitated our first workshop at iDOCS. We divided a packed room into small groups and asked each group to select one project to map/visualize. We offered a list of prompts and immediately the room was alive with suggestions and ideas for additional areas to reflect upon. The session was generous and generative and demonstrated the need for such collaborative reflexive spaces.

We were standing in front of a whiteboard in Liz’s study in Montreal, and Dorit was listing turning points in the process of making Jerusalem, We Are Here (2016). JWRH is a participatory interactive documentary that digitally inscribes Palestinians into the neighborhoods from which they were expelled during the 1948 war. Liz had spent the week before “mapping” key moments and turning points in her project The Shoreline (2017), an interactive documentary on the impacts of over-development and sea level rise that she co-created with students, documentary makers and educators in more than forty coastal communities. The reflection exercise Liz had undertaken was guided by Leith Sharpe of Harvard University.

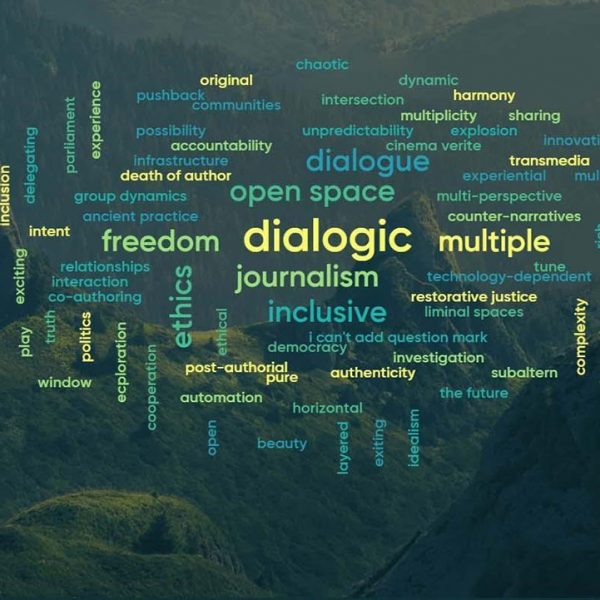

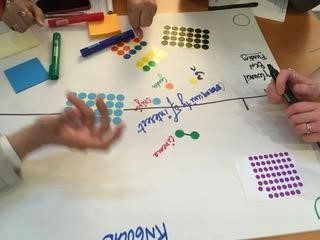

On the whiteboard, Dorit drew an axis for the life span of the JWRH project, and then started adding sticky notes, bubbles, arrows, and text. We realized quickly the most interesting moments in Dorit’s emerging visualization were the messy areas on the board: unexpected opportunities where participants changed roles, where output and media were reconfigured, and where ethical concerns were at the forefront. Each of Liz’s follow up questions led to more insights and information on the board.

Having a chance to process together the highs and lows, the mishaps and turning points, and the lingering concerns was not only insightful but affirmed our shared conviction that process is as important as product. We quickly asked ourselves: can we use visual mapping to help convey the complexity, messiness, and non-linearity of participatory work to ourselves and to others? And we discovered that a non-linear mapping visualization provided a rich testament to the nature of participatory processes.

That session instigated four years of collaboration as rich and complex as those creative projects we were mapping. Like all co-creative processes, we were engaging in co-learning, a slow conversation rooted in our situatedness, our teaching, our research-creation practice, and in contemporary political realities. To date, this ongoing collaboration has included workshops, class visits, the creation of an online tool, and a new opportunity to co-teach.

Our next step was to try this out with our graduate students. We were both teaching courses on research-creation and we quickly realized that to benefit students—who are at the beginning of their projects—we had to adapt the exercise from reflection to planning. The tool was even more effective than we had anticipated and we witnessed students rethinking the relationship between participants, audiences, and their own process.

We now knew that the project was useful both as a reflection as well as a planning tool, and we started thinking of how to share it more widely, so first we had to find out what tools, articles and resources were already out there. In the Fall of 2018 we attended the Collective Wisdom symposium hosted by the MIT DocLab, where we met the authors of the “The PreNups: What Filmmakers and Funders Should Talk about Before Tying the Knot” and the creator of the Dot Connector card set to assess impact. These insightful professional tools inspired us, and also clarified that there are fewer tools for students who wanted to ensure they were working ethically and responsibly.

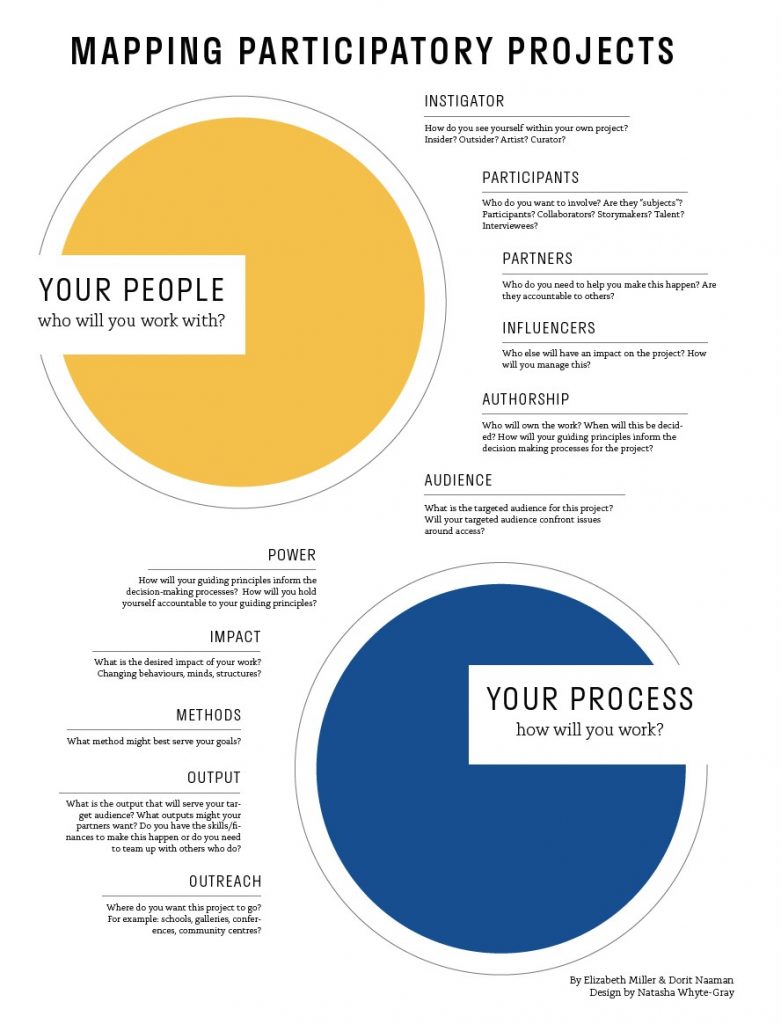

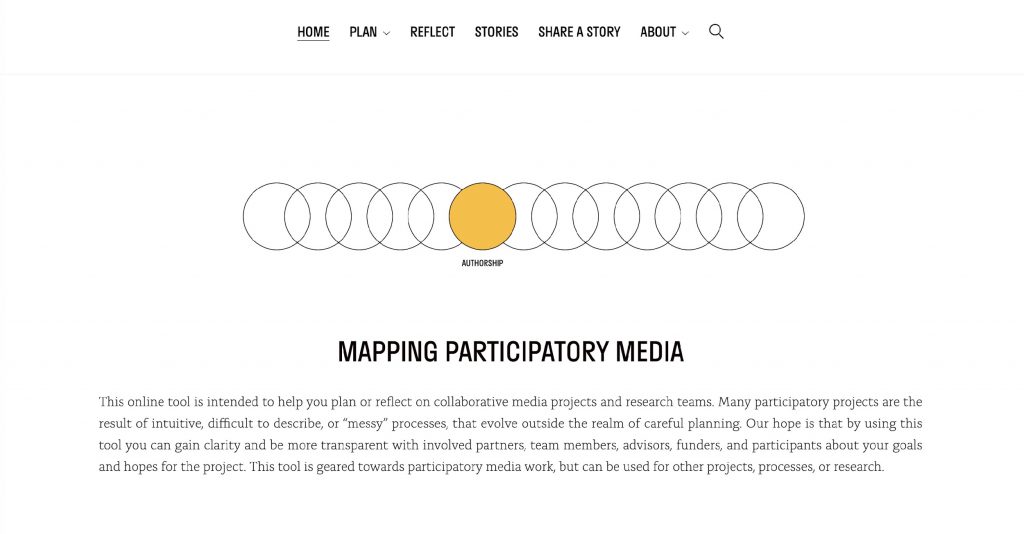

We decided on a website to host the mapping and planning tool and brought on web-designer Natasha Whyte-Gray who was as equally invested in design as she was in our method. Flexibility and interaction had been key to our process and would need to be integrated into the online platform. We divided the tool into two parts: “your people” and “your process,” and under each of these there are sub-categories that could be mapped (such as instigator, influencers, audience, output, impact, etc.). Each sub-category contains questions, stories, and resources.

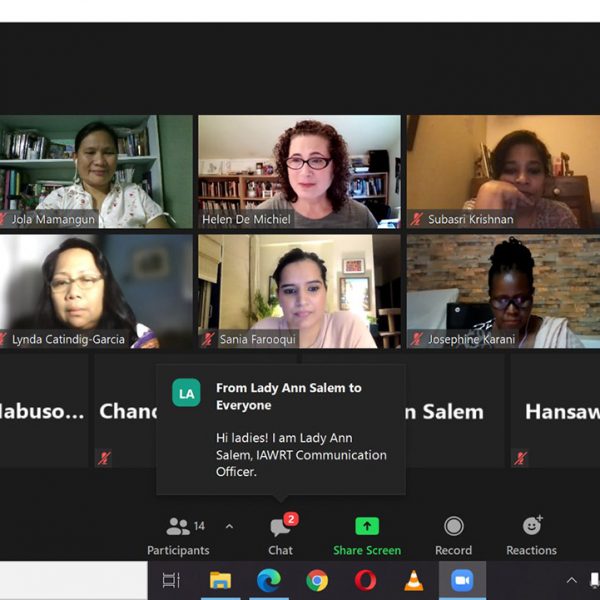

During the pandemic we both participated in Zoom meetings convened by Patty Zimmermann and Helen De Michiel. Once a month we met on Zoom with documentary filmmakers and educators who were deeply committed to participatory work, and shared our challenges in teaching remotely. Ironically, it was the first time we had the opportunity to discuss participatory production pedagogy with like-minded practitioners, and it was thrilling, despite the pandemic gloom. In our ongoing work sessions to develop the tool, we also shared teaching strategies and experiments, and often brainstormed solutions for problems.

Then it occurred to us that the robust working document we had developed with all of the content for our online tool looked a lot like a syllabus, with learning goals, modules, readings, case studies, and guiding questions. And suddenly with pandemic conditions, the idea of a remote co-created and co-taught course not only seemed feasible, but necessary. We proposed to our respective universities a co-taught remotely offered course, and it was approved with enthusiasm.

It seemed ethically appropriate to emphasize situatedness—for students to engage from wherever they were working, and with guests who might “visit” from their own location of practice. What was unfathomable before the pandemic, has now opened doors for grounded, cross-cultural, and situated shared learning spaces, so apt for this kind of work. The course is titled “Ethics, Care and Participatory Culture” and will be offered in the Winter of 2022 at Concordia University and Queen’s University. We cannot wait to co-learn with our students.

We hope this tool might also be useful for the Visible Evidence community, as we plan a future salon where practitioners can workshop projects in the company of other brilliant documentary makers and scholars. Please fill out the online form if you are interested in joining!

# # # # #

Elizabeth (Liz) Miller is a documentary maker and professor interested in new approaches to community collaborations and documentary film as a way to connect personal stories to larger social concerns. She has organized and led media institutes and workshops with a range of groups (youth, senior citizens, human rights advocates, refugee organizations, teachers, water experts) in video advocacy, digital storytelling and media production. Her films/educational campaigns on timely issues such as water privatization, immigration, refugee rights and the environment have won international awards, been integrated into educational curricula and influenced decision makers.

Dorit Naaman is a documentarist and film theorist from Jerusalem, and a professor of Film, Media and Cultural Studies at Queen’s University, Canada. In 2016 she released an innovative interactive documentary, Jerusalem, We Are Here, offering a model for digital witnessing. Dorit’s in-production collaborative project The Belle Park Project is situated in Kingston, Ontario, and continues her interest in using creative practice to make visible, legible and audible that which has been actively erased or obfuscated. Dorit is publishing on participatory media, and has previously researched film and media from the Middle East, specifically on nationalism, gender and militarism.

# # # # #