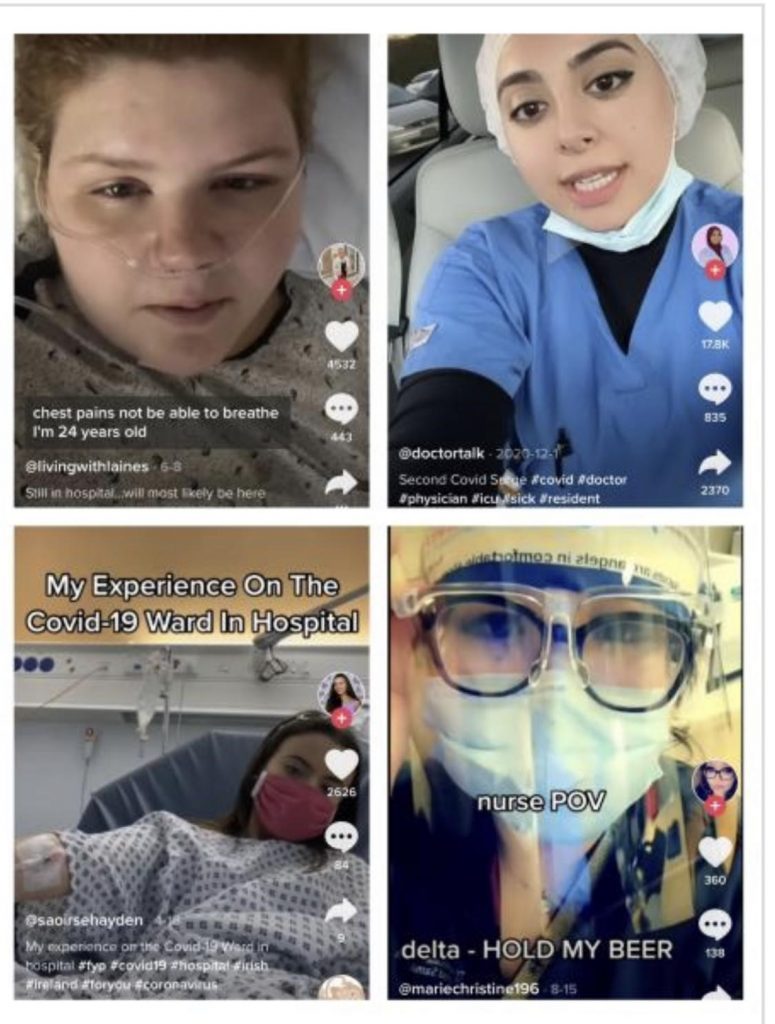

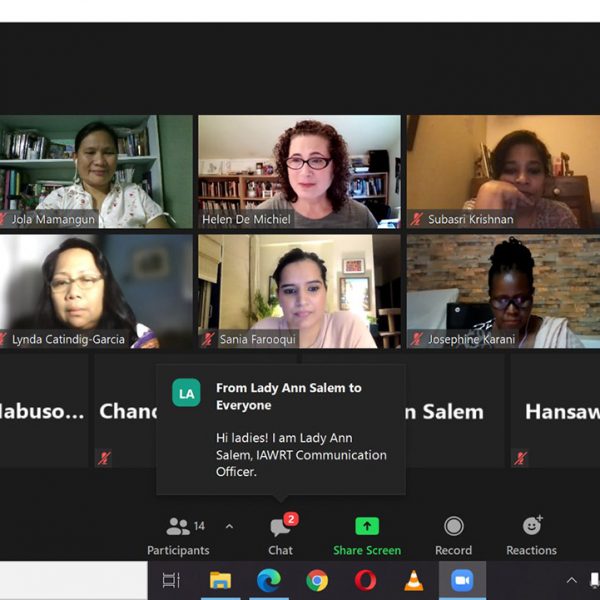

These interactive conditions of digital culture align with a significant historical conjuncture: a pandemic crisis, growing political and social upheaval, historic uprisings around racial injustice, economic crisis, dissatisfaction with representative government, and disillusionment with state institutions. Struggles against racial injustice have become more complicated in the shadows of pandemic isolation where the screen is our primary connection to the world and its unfolding conflicts. From March 2020 and into the present, face-to-face life was dismantled and what emerged was a digital approach to collectivity, where the influence of the screen and user generated content became a spotlight of public life. The vivid documentation of racist conflicts captured on mobile recording devices widely circulated in pandemic isolation, as we looked out into the world through our screens via Twitter, TikTok and Instagram.

Participatory co-creation and community media practices can be harnessed to correct the tendencies of problematic visual tourism and surface-level transformation endemic to commercial documentary industry practices.

While the documentary impulse is frequently conceptualized as a democratic tool with civic potential, the way it functions in the process of social change is variable, contingent, and riddled with ethical considerations.

For most of cinema history, media makers fortunate enough to learn the craft with easy access to equipment to produce visual media have historically come from a privileged class. Filmmakers could gain access and/or exposure to grassroots stories but under tenuous conditions from outsider perspectives.

The advocacy film is a time-honored tradition in documentary history, made specifically for the aims of democratic exchange. Yet the commercial industry has been slow in confronting its own political tourism legacies, recording social injustices where the most significant benefit of production serves filmmakers rather than the communities on the screen.

Just before the pandemic the fissures of these tensions began to surface. At the 2019 True/False Film Festival a student activist disrupted a Q and A session following the screening of The Commons, a documentary made by white filmmakers about Black-led protests to remove the Silent Sam confederate statue on the UNC-Chapel Hill’s campus.

Shocked by the misrepresentation of activists in the documentary, activist Courtney Symone Staton read a statement to the festival crowd demanding action by “documentary filmmakers, funders, programmers, and audiences to question and address the recurring and systemic problem of racist, extractive and colonial filmmaking practices.” The faces, bodies, voices, and words of activists were “being shown to hundreds of people without their consent and depicted through a colonial gaze.”

In this historical moment where we must correct the problematic tendencies of documentary tourism, the bodies that push the buttons matter– and so do their intentions, examined or latent.